Rauh Jewish Archives at the Heinz History Center

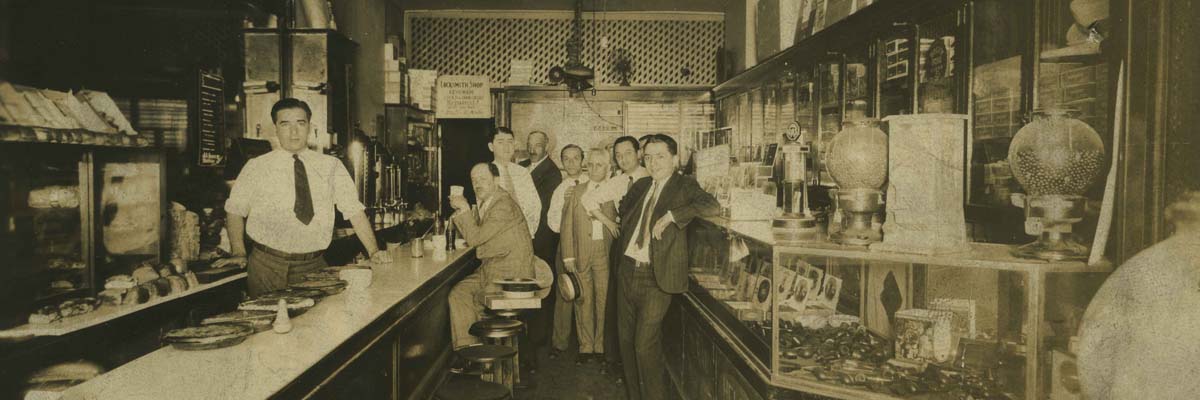

For nearly a century, Jewish commercial activity in Western Pennsylvania centered on a nine-block stretch of lower Fifth Avenue, in the Uptown section of Pittsburgh.

“The Avenue,” as it was called, ran from about the 600 to the 1500 blocks of Fifth Avenue, which covers an area from the Crosstown Boulevard to Fifth Avenue High School. Between the 1880s and the 1980s, thousands of business passed through the Avenue, some lasting for decades and others for only a few months. Most were Jewish-owned businesses, particularly wholesalers that supplied stores throughout the region with essentials such as clothing, linens and house wares. These wholesale businesses were strictly commercial enterprises, but their work created communal bonds that reached far beyond the Avenue and continued long after the district was gone.

1880-1920

The earliest Jewish wholesalers on Fifth Avenue were largely Eastern European immigrants who had built their businesses from humble beginnings. Many, such as Philip Loevner, started out as peddlers. After immigrating to Pennsylvania from Austria-Hungry in the 1890s, Loevner and his brother-in-law Gus Trau rode trains from town to town along the Allegheny River, peddling long underwear from suitcases. About 1897, they opened Trau & Loevner, a Fifth Avenue men’s store that spent nearly 70 years at 1029 Fifth Avenue before moving to its current home in East Liberty. Some wholesalers started out working for other people. James Cohen immigrated to Pittsburgh from Poland in 1885 and worked for a merchant until he started the James Cohen Company about 1890. His shoe store stayed on Fifth Avenue for nearly a century.

These men started stores, in part, to have storage space. Cohen was a “jobber,” or someone who traded in “job lots,” collections of merchandise purchased as a unit and often sold for at a bargain price. While peddlers could carry their goods in packs, jobbers needed a place to store their larger collections of merchandise. By 1914, Cohen owned three adjacent properties in the 1000 block of Fifth Avenue. Soon he built the three-story “Pittsburg Jobbing House” at 1021 Fifth Avenue. As other peddlers and salesmen became jobbers, they built or bought warehouses along the Avenue, which eventually turned the area into a wholesale district populated primarily by Jewish-owned businesses.

There were similar districts on Penn Avenue and Fourth Avenue in the heart of downtown, but the Fifth Avenue district in Uptown was unique. It had assumed some of the flavor of the neighboring Hill District, which was the center of immigrant Jewish life in Pittsburgh. A 1917 survey of Uptown by the Pittsburgh Council of the Churches of Christ reported: “In business, the dry goods stores are practically monopolized by the Jews, and they are becoming numerous in nearly every other line of business. They are the most ambitious to get an education, and many are becoming doctors, dentists, lawyers, artists, etc., and they furnish many other leaders in the community life; four out of five picture shows, for instance, are run by Jews.”

Between 1880 and 1920, the Jewish population of Pittsburgh went from 2,000 to 53,000, and the commercial population of the Avenue grew six-fold, from about 43 businesses to about 272 businesses, according to a population survey by researcher Amy Lowenstein. The Avenue became predominately Jewish during this time. In 1883, Jews owned only 35 percent of the businesses in the district. By 1920, almost 75 percent were Jewish-owned. With this growing Jewish population came Jewish institutions. The Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, the National Council of Jewish Women, the Montefiore Hospital Association and the United Jewish Relief Association, among many other Jewish groups, all had offices on the Avenue in their early years.

In addition to selling goods at retail prices directly to the public, the earliest Fifth Avenue jobbers also sold goods at wholesale prices to small-town stores throughout Western Pennsylvania. Because many store owners were Jewish, sales calls sometimes contained a social element. As a boy, Mel Pollock watched salesmen lug merchandise from the train station to Pollock’s, his parent’s department store in Gallitzin, Pa., near Altoona. “There was not always a train that you could get out of Gallitzin,” Pollock said in a March 2007 oral history. If a customer came into the store during a sales call, the salesman might end up waiting around for hours before he could show the owners his wares. “It would be dinner time, and so we had dinner and they stayed at the house,” Pollock remembered.

Seeking to capitalize on this regional trade, the Jewish Criterion began a monthly advertising section in March 1919 called “Merchants of Near-by Towns: BUY IN PITTSBURGH!” The newspaper chided merchants for using Pittsburgh wholesalers only to “fill in” their stocks while patronizing East Coast wholesalers for the bulk of their supplies. As Western Pennsylvania population grew and regional trade expanded, the relationship between small town merchants and Fifth Avenue jobbers strengthened.

1920-1950

With this growth came professionalism. The scrappy “jobbers” became influential “wholesalers” who attended trade shows and maintained ties with East Coast and Midwest manufacturers. The “peddlers” became “traveling salesmen” who covered a territory stretching for 150 miles in every direction from Pittsburgh. The Fifth Avenue business owners who once walked to work from the Hill District now commuted from homes in the East End. Some early Uptown businesses like the Frank & Seder Department Store, the furrier Max Azen and Sam the Umbrella Man even left the Avenue to become much more well known at downtown locations.

By the 1930s, the Avenue was a self-sufficient neighborhood. Alongside the wholesale houses were accountants, banks and insurance brokers to manage business affairs and advertising agencies and photographers to handle marketing. There were also neighborhood amenities such as restaurants, bakeries and butcher shops; tailors, launderers and barbers; doctors and dentists; filling stations, movie theaters and a bowling alley.

This sense of community eased advancement. Jacob Fienberg spent 20 years as a traveling salesman for a Fifth Avenue dressmaker before opening a wholesale ladies clothing store in 1931. He and his partner started their business with a $10,000 loan from the Washington Trust Company, which the Fifth Avenue bank issued based mostly on Fienberg’s reputation. “I says, ‘I ain’t got no collateral to give you, nothing to show for it, just my name,’” Fienberg recalled during an oral history conducted by the National Council of Jewish Women. “He said, ‘I know you so doggone well, I couldn’t turn you down.’”

The commercial and community interests of the Avenue sometimes intertwined. In 1903, a group of merchants founded the Pittsburgh Wholesale Credit Association to promote better business practices. By 1936, the membership was composed almost entirely of Jewish-owned businesses, and two-thirds of those businesses were on Fifth Avenue. The association maintained offices in the Washington Trust building, supported a full-time business manager and kept track of the creditworthiness of retailers. It served a communal function, too. In addition to hosting an annual banquet, the members sold war bonds during World War II and later dedicated an Honor Roll and Plaque of the veterans among its ranks.

The owners of these businesses also promoted causes outside of the association. Officers such as Robert E. Comins and Emanuel Spector raised money through the Mercantile Council and the Independent Retailers Division of the United Jewish Fund. Many Fifth Avenue business owners were active in local synagogues; the wholesaler Louis Gordon was president of Tree of Life Congregation and Henry Kaufman, of the Fifth Avenue Notions House, was treasurer of Beth Hamedrash Hagodol. The yearbooks of Hillel Academy are full of advertisements for Fifth Avenue businesses. These businessmen also supported nonreligious causes. In the late 1950s, the Dinovitz Clothing Company sponsored a semi-pro basketball team made up largely of Jewish players from Fifth Avenue High School.

And the Avenue helped sustain Jewish life across Western Pennsylvania. Every Sunday, small town retailers visited the Avenue to restock their merchandise, buy kosher food and connect with old friends. There are several accounts of young salesmen meeting future spouses through connections made on the Avenue. “Fifth Avenue was probably my first exposure to what might be called a ‘Jewish community,’” Allen Zeman, whose family ran The New York Store in Evans City, Pa., recalled in a November 2007 oral history. “There were several kosher meat markets along Fifth Avenue. We would buy meat for the week and hurriedly get it packed back to Evans City so that we could freeze it. We didn’t have too much of an organized Jewish life in Evans City, but strict kosher in the home is something that we adhered to. It was a way of building identity.”

1950-1980

The Avenue declined for political, cultural and economic reasons. Using eminent domain, the Urban Redevelopment Authority demolished three blocks on one side of Fifth Avenue in the late 1950s to make room for Chatham Center. The demolitions displaced many businesses. Between 1953 and 1960, the commercial population of the district dropped from 280 to 152, its smallest population since 1895.

A cultural shift was also underway. As small-town Jewish families stopped keeping kosher or started using the weekends to relax from the daily grind of retailing, the once thriving Sunday business declined. Once, wholesalers could cover an entire week’s worth of expenses from Sunday business, but increasingly small-town merchants only came to the Avenue for “hurry up” goods, things they needed more quickly than express mail could accommodate. The wholesalers had to depend on the efforts of their traveling salesmen.

The economic threat came from changes in the industry. First, the decline of mills and mines prompted an exodus from small towns, making it harder for retailers to make a living. Then, manufacturers started bypassing the “middlemen” by sending representatives to sell directly to small-town retailers, without a wholesale mark-up.

In time, mass-merchandisers brought costs down even further through economies of scale. “Several years after the Second World War, the small stores started to go out of business,” Mark Loevner said in a 2006 oral history. “Then you started to get Army-Navy stores to take their spots, their locations, and then eventually even those kinds of stores went out of business. And then you started to get the mass merchandisers. Instead of having W.T. Grant, you had Grant Cities. Instead of having Woolworth, you had Woolco stores.” As the mass merchandisers arrived, Trau & Loevner switched its focus to screen-printed apparel, which allowed the company to survive the changes in the retail industry.

Wholesale businesses were still operating on the Avenue by 1980, but the district was gone. Some buildings were converted to law offices and restaurants, others were demolished for parking. By 2008, when construction of the Consol Energy Center eliminated several more blocks of the Avenue, most of the wholesalers were gone. Today, the only physical remnants of the Avenue are some faded signs. The economic legacy is greater. Over the course of a century, the Avenue lifted hundreds of Jewish families into the middle class.